PUBLIC DISCUSSION

From Aurora to Geospace

Hanna Husberg, Agata Marzecova, Camilla Larsson, Liv Strand

Östra Galleriet, Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Stockholm, 14th March 2020.

* * *

Through a focus on the ionosphere and near-Earth space, the research exhibition From Aurora to Geospace looks at how environmental imaginaries emerge, how atmospheric phenomena are made visible through technoscientific infrastructures and how these contribute to novel ways of perceiving the environment. In order to map and conceptualise regions of the atmosphere that are imperceptible and inaccessible to human sensing, such as the upper atmosphere, scientists have developed numerous representations and practices. Rather than observing atmospheric phenomena as such, the project builds upon field trips to ionospheric radar infrastructures located in northern Finland, Sweden and Norway, and explores the instruments, historical circumstances, events and ideas that make them visible, and that contribute to the construction of novel atmospheric imaginaries and sensibilities. Working in the interstitial space between art and science, the installation makes use of different elements and material forms to reflect upon how atmospheric knowledge is made and materialised through processes of imagination and representation.

In this public conversation with Camilla Larsson, curator and writer, and Liv Strand, artist, both board members of the Nordic Art Association (NKF) in Stockholm, where Husberg and Marzecova spent a month preparing the exhibition, the four discuss the interdisciplinary process behind the exhibition. The discussion was held at the opening of the From Aurora to Geospace exhibition at Östra Galleriet, Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Stockholm on March 14th 2020, in the context of Husberg’s year long Bernadotte Scholarship at the Academy.

* * *

Liv:

The Nordic Art Association (NKF) is an organisation of visual artists and curators in the Nordic countries aiming to create networks. The Swedish section, in which I and Camilla are board members, has a Guest Studio in Stockholm which is used to support collaborations between local artists and their foreign collaborators. This February, Hanna has been a host for Agata, so the work we see here has at least partially been produced or discussed during this NKF residency.

Camilla:

We often host events at the guest studio as a way of sharing the work of the residents and fostering a broader discussion. In this case, as Agata and Hanna were preparing a spatial and site-specific installation at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts we decided to have our discussion here instead. Coming here, we are drawn in by these lines, orbiting around a circle, the planet, there are different categories of images and modes of presentation. Could you start by telling us about your process in working on this exhibition? And what are the different elements we see?

Hanna:

The month-long residency at the NKF preceding this exhibition was an important period for us to come together to work out the materialities of the installation we’re sitting in here. The project was initiated two years earlier, and started with the Ars Bioarctica residency in Kilpisjärvi, located next to the three-border point connecting Finland, Sweden and Norway. You can see the landscape in one of the large-format photos on the wall.

As we were doing research prior to the residency we found out that the Fennoscandian arctic is an important region for studying the upper atmosphere. In Kilpisjärvi we were actually based at the biological station. The site, however, lies in-between three locations that are significant for ionospheric radar research —Tromsø , Kiruna and Sodankylä — and since some years a prototype for the future-generation ionospheric radar is also set up in Kilpisjärvi. So, it’s a place where the up-coming technology is currently being tested. In a sense, the whole region can be conceived as this natural laboratory for geophysicists experiments — radio signals are sent into the upper atmosphere from Tromsø, and the other two radars, located several hundreds of kilometers away measure the reflected waves.

The three ionospheric radar research stations as well as the prototype in Kilpisjärvi are represented in the installation using large format photography that frames some of the radar infrastructure within the landscape.

As we were doing research prior to the residency we found out that the Fennoscandian arctic is an important region for studying the upper atmosphere. In Kilpisjärvi we were actually based at the biological station. The site, however, lies in-between three locations that are significant for ionospheric radar research —Tromsø , Kiruna and Sodankylä — and since some years a prototype for the future-generation ionospheric radar is also set up in Kilpisjärvi. So, it’s a place where the up-coming technology is currently being tested. In a sense, the whole region can be conceived as this natural laboratory for geophysicists experiments — radio signals are sent into the upper atmosphere from Tromsø, and the other two radars, located several hundreds of kilometers away measure the reflected waves.

The three ionospheric radar research stations as well as the prototype in Kilpisjärvi are represented in the installation using large format photography that frames some of the radar infrastructure within the landscape.

Agata:

We began by exploring arctic atmospheric phenomena in more general terms, in particular aurora borealis. At that time, we didn’t realise that studying auroras through modern scientific methods actually requires studying geospace, the whole region stretching from our planet to the sun, including a long tail ‘behind’ the planet. This is because processes contributing to the aurora take place in this region. In this scientific interpretation, aurora is conceived as the coming together of forces from the magnetosphere, the ionosphere and the sun’s particles.

Located under the auroral oval, the Fennoscandinavian arctic is well positioned to study auroras and the outer atmosphere, things that we generally take for granted from textbooks. During our fieldwork, we asked different people what is aurora and how it works. The atmospheric scientists often sketched a diagram on a piece of paper or they googled it to show us. They needed this boundary space to explain their ideas. We were surprised to see that their notion of the planetary processes incorporated the whole domain of Sun-Earth interaction — this was their playground. More commonly, Earth’s boundary is visualised by the ‘Blue marble’, a photograph that was equally produced in scientific contexts. The photographic representation offered by this emblematic image, however, puts forward a distinctly different notion of a planetary boundary, constrained to what is visible to the eye. Because we wanted to visualise these scales, we decided to reproduce this scientific diagram on the gallery floor using masking tape.

Located under the auroral oval, the Fennoscandinavian arctic is well positioned to study auroras and the outer atmosphere, things that we generally take for granted from textbooks. During our fieldwork, we asked different people what is aurora and how it works. The atmospheric scientists often sketched a diagram on a piece of paper or they googled it to show us. They needed this boundary space to explain their ideas. We were surprised to see that their notion of the planetary processes incorporated the whole domain of Sun-Earth interaction — this was their playground. More commonly, Earth’s boundary is visualised by the ‘Blue marble’, a photograph that was equally produced in scientific contexts. The photographic representation offered by this emblematic image, however, puts forward a distinctly different notion of a planetary boundary, constrained to what is visible to the eye. Because we wanted to visualise these scales, we decided to reproduce this scientific diagram on the gallery floor using masking tape.

Camilla:

For the diagram you used an illustration that someone showed you?

Agata:

The diagram we use is the accepted illustration of how the sun-planetary space works. This is how you would have it in science textbooks. For geospace scientists, it is how they imagine space.

Camilla:

And the colours how did you choose them? You also have this two-channel video and historical images displayed on museal stands. What kind of perspective do they put forward?

Hanna:

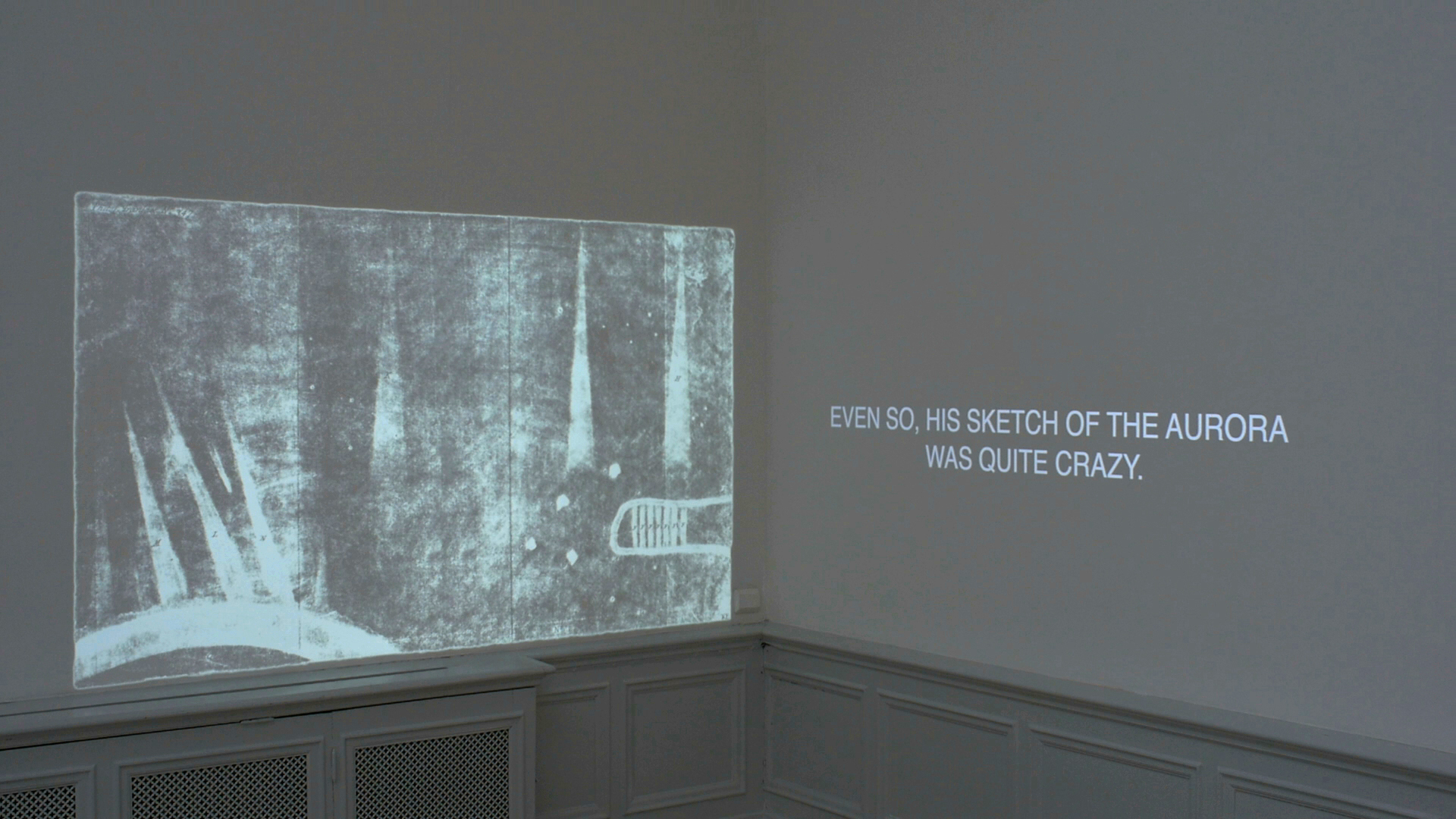

I’d say we are quite much in-line with the colours used in the published diagrams. We haven’t looked into why the scientific illustrations use certain colours rather than others, but quite often the colour schemes use blue and purple, and for natural reasons the sun is quite often yellow. We took some liberties and there were also variations in the diagrams we found, you can see a couple of them in the two channel video essay that reflects some of the stories and narratives we encountered during our field trips, and that is also connected to the aluminium prints on the stands.

![]()

Reflecting the title of the exhibition (From Aurora to Geospace) the video is structured alphabetically from A to G. Starting with Atlas of Auroral Forms it moves on to Black-box, evoking the black box of science, as this is the principal means we have to access knowledge about geospace. Then, there is C for Communication. The ionosphere — the atmospheric region where auroras take place — is also a part of the atmosphere that was discovered because it bounces back radio waves. So it is very strongly connected to the development of technology, science and all the telecommunication we are using today. Then we have D for Data and Diagrams, followed by E for Experimentation and F for Forecasting Futures. Here, we highlight phenomena such as space weather, and bring up the next generation radars, which will soon be deployed in the region, and that will significantly shift how science is done. Finally, we end with G for Galaxy, Geospace and Ground. Even if we are talking about near-Earth space, so not outer space, we highlight the continuity towards radiogalaxies, which are for example used for the calibration of geospace instruments. So starting with auroras that generally occur 80 km or higher in the ionosphere, the video includes regions as far as 60 million light years away. Moreover, we also include the ground, as this is where much of the instruments, infrastructure and people are located.

Reflecting the title of the exhibition (From Aurora to Geospace) the video is structured alphabetically from A to G. Starting with Atlas of Auroral Forms it moves on to Black-box, evoking the black box of science, as this is the principal means we have to access knowledge about geospace. Then, there is C for Communication. The ionosphere — the atmospheric region where auroras take place — is also a part of the atmosphere that was discovered because it bounces back radio waves. So it is very strongly connected to the development of technology, science and all the telecommunication we are using today. Then we have D for Data and Diagrams, followed by E for Experimentation and F for Forecasting Futures. Here, we highlight phenomena such as space weather, and bring up the next generation radars, which will soon be deployed in the region, and that will significantly shift how science is done. Finally, we end with G for Galaxy, Geospace and Ground. Even if we are talking about near-Earth space, so not outer space, we highlight the continuity towards radiogalaxies, which are for example used for the calibration of geospace instruments. So starting with auroras that generally occur 80 km or higher in the ionosphere, the video includes regions as far as 60 million light years away. Moreover, we also include the ground, as this is where much of the instruments, infrastructure and people are located.

Agata:

The span auroral scientists refer to is from 10 km to something very abstract. Apparently, they calibrate the instrument by focusing on a distant dead star. It's funny that something so very poetic, even spiritual, has this very pragmatic use.

To add two things. First, the video uses snippets of conversations that we had with people who work with ionospheric and auroral research, whether historians or scientists.

Then, to follow up on materials for the diagram, we used masking tapes from local hardware stores. They use different colours for different purposes, blue for windows and pink or purple for sensitive areas. So while the choice of colours was very limited, they happened to match our diagram. This also resonates with the serendipities that are regularly featured in the history of science. One of the stories we were told is that the radiogalaxy was discovered because there were some strange signals from space affecting radio communication. So what we today understand as the radiogalaxy, which is quite a significant concept, was first detected and perceived as a disturbance or noise. So, we were happy to include this kind of happenstance also in our process.

To add two things. First, the video uses snippets of conversations that we had with people who work with ionospheric and auroral research, whether historians or scientists.

Then, to follow up on materials for the diagram, we used masking tapes from local hardware stores. They use different colours for different purposes, blue for windows and pink or purple for sensitive areas. So while the choice of colours was very limited, they happened to match our diagram. This also resonates with the serendipities that are regularly featured in the history of science. One of the stories we were told is that the radiogalaxy was discovered because there were some strange signals from space affecting radio communication. So what we today understand as the radiogalaxy, which is quite a significant concept, was first detected and perceived as a disturbance or noise. So, we were happy to include this kind of happenstance also in our process.

Liv:

Can you tell us more about the role of disciplines and how you deal with the notion of expertise in this project? In the different places that you visited, you met a lot of experts and people involved with this kind of research. How has it been for you as artists to meet them and their knowledge?

Hanna:

We have met a few different scientists. I get a sense that they enjoy talking to artists, maybe because there is a freedom in it and not so many expectations. They get to talk about what they are really interested in and seem happy to find others who are also interested in what they do, although from a different perspective. We also have different backgrounds. I am a visual artist working with air and atmosphere while Agata has a scientific background, as well as in photography and new media, so we are also able to ask different kinds of questions. We often set up a situation which is more in-line with a dialogue rather than an interview. People with whom we talk are often curious about why we are looking at these questions, so we might start talking about environmental imaginaries and our questions, which is something that also triggers their interest.

Agata:

I think that the research element was an important factor. We were researching atmospheric imaginaries, coming with our own set of questions. Intuitively, I think the research provides a difference to the didactic approach, when you have an expert explaining the phenomenon to the ‘uninformed’ audience. This is not to say that our field-interviews were not didactic. We definitely had experts telling us how things work, and explained many things which we didn’t know. Even though I was trained as a scientist, a lot of things were new to me, which also points at the overspecialisation of science. But I’d say that the research element, asking questions back and forth, and together, generated an interesting difference to a merely didactic setting.

Camilla:

You also have this historical layer, and met some historians. What does it bring to the project?

Agata:

Yes, we wanted to talk not only to scientists but to people from different spheres and disciplines. For example, we met historians from Tromsø University, who provided perspectives on the longer histories of auroral research and the related imaginaries that stretched back to the 16th century. This was a particularly interesting historical moment, because in 1706, northern lights reappeared after an absence of more than a hundred years — there were very little auroral events during the whole medieval times due to low solar activity. As historian Kira Moss pointed out, this was during the pre-photographic era, so you have lithographic representations, while we had to wait until the early 20th century before photographic documentation of the phenomena was made possible.

Hanna:

That was also a very important era for the Nordic nation states, and for scientific development in this part of the world. Auroras were in the spotlight of knowledge production. Every respected scientist wanted to present explanations of what the auroras were. At that time many of the scientists were from France, Italy or England, so far from where you would normally see auroras. Most of them had seen it maybe once, if even that. Moreover, people at southern latitudes would see aurora from a different perspective, because only very strong auroras are visible there, and then you would see them as red. So you would see them very differently than how local people in the auroral regions would see it. This also prompted Sweden, for example, to actively work with these issues. There was this attitude like ‘this thing should belong to us, we should be doing the science’. In part, this was possible because the Fennoscandian arctic has a relatively mild climate in comparison with other places that have aurora. Many people live there. There are universities, communication and infrastructure — you can ship-in large antennas. So, it is much easier to do research there than doing it in Siberia or Alaska, places that have the same auroras but are not as accessible.

Camilla:

So, you met a lot of scientists with different sensibilities of how to think about that specific phenomena, whether historically, or today, influenced by these highly technical instruments. What would you say, what kind of sensibilities are you working with as artists? What is the difference between the scientific and artistic approach?

Agata:

I think for us this project brings together a deep interest and also discontent with the reliance on expert science. How we imagine the atmosphere is very much given to us by a certain group of people or institutions. There is not much of back and forth. This is not a democratic or otherwise inclusive discussion. On the one hand, we need to stand in defense of science, which is under various attacks, on the other hand, the increasing commercialisation and overspecialisation of scientific enterprise is problematic. For us, it is interesting that there is a very small group of people and very specific instruments that define our knowledge about the atmosphere. If there would be different people and different infrastructure, then we might have a different understanding of outer space or even the layers of the atmosphere. While we haven’t fully explored this in our project, it is something we do not want to ignore. This is not to say that science is bad because it was made by men of a certain status. It is, however, important to remember that other knowledge is not heard and acknowledged. I don’t think we have answers to how one should work with it and address this critically, but we are exploring methods on how to engage with it.

The title of our long term project is ‘Towards atmospheric care’ so our interest is to explore how to care for imperceptible environments and how to meaningfully consider this representational yet material sphere between what is perceptible and imaginable to us, and the outer space that, while difficult to comprehend, is permeated with satellites, other technologies and environmental processes that condition our lives. While we do not have an answer, this is a starting point of our exploration.

The title of our long term project is ‘Towards atmospheric care’ so our interest is to explore how to care for imperceptible environments and how to meaningfully consider this representational yet material sphere between what is perceptible and imaginable to us, and the outer space that, while difficult to comprehend, is permeated with satellites, other technologies and environmental processes that condition our lives. While we do not have an answer, this is a starting point of our exploration.

Hanna:

As we are dealing with phenomena so vast that you cannot grasp them directly, the question of visibility frequently reemerges. Relatedly, the construction of imaginaries and ways of thinking is extremely important. Inquiring into how these imaginaries come about has been a main motivation of the project. This exhibition is the first actual outcome stemming from the research trips we have done these past two years and our project will still evolve. The installation is also a material element for continuing to think further from here.

Liv:

I don’t know if you agree, but in a sense you have made a room for knowledge production based on visual elements and images from different periods of time that you have come across through your research and that you feel are important. Working with researchers at the Karolinska Institute, I noted that in all their discussions, also amongst each other, they always needed an image that would allow them to say “hey, look here …”. So it’s interesting to see the occurrence of such images here. Today, we’ve heard a lot of explanations from you. But, I think what is interesting with this exhibition is that it uses different visual elements to expand our vision and sensibilities in a meeting with a knowledge that at some levels we might understand and maybe at some level we don’t. You provide some texts and some quotes but you also hold back on information. How much have you been thinking about this?

Agata:

It was important for us not to make an informational or museal exhibition of artefacts with explanatory captions. Rather, we wanted to share our experience of uncovering the auroral histories. The exhibition gives people space to incorporate or deepen their own knowledge and experience about things like aurora and near-earth-space, but not in a prescriptive, uniform manner. Definitely, we are not against didactics. But in this context we wanted to keep the notion of atmosphere unstabilised, leave-in the sense of the historical moment, of contingency and changeability. We wanted to include a plurality of things, but we also know that many perspectives are left out. At least, we have curated a glimpse into different views on the auroral phenomena and geospace that is informed by our particular field experience.

![]()

* * *

Liv Strand is a Stockholm-based artist who, through installation, writing, guided tours, workshop or sculpture, gives form to the aspiration of re-shaping shapes yet-to-come. Using different formats her work aims to assemble a space for temporary negotiations about the art of staying on the surface, how to blend into a striped space or how the structure of nation states frames our lives. She is the co-initiator of Salon Material, running since 2011, and of feminist sound art project Larm (2004-08).

Camilla Larsson is an independent curator, writer, and lecturer based in Stockholm. She is a member of the network Skräddare som rebell (Tailor as rebel) that consists of artists and curators working with their shared history of coming from families working with textile. She is also a PhD-candidate in Art History at the School of Culture and Education, Södertörn University.

From Aurora to Geospace is developed as part of Towards Atmospheric Care, a long-term art-led research project by visual artist Hanna Husberg and researcher in ecology, photography and new media Agata Marzecova. The research and installation has been developed through the support of several artistic residencies and institutions, notably residencies at Ars Bioarctica Residency (Finnish Bioart Society, Kilpisjärvi, 2018-19), Torpet, Pro Artibus (2019), NKF residency, Stockholm (2020), Husberg’s Bernadotte scholarship at the Royal Art Academy, Stockholm (2019-20), Marzecova’s HIAP residency and a generous project grant from the Arts Promotion Center, Finland (2020). The project was first exhibited at Östra Galleriet, Royal Art Academy, Stockholm (14.3-14.6.2020).

Camilla Larsson is an independent curator, writer, and lecturer based in Stockholm. She is a member of the network Skräddare som rebell (Tailor as rebel) that consists of artists and curators working with their shared history of coming from families working with textile. She is also a PhD-candidate in Art History at the School of Culture and Education, Södertörn University.

From Aurora to Geospace is developed as part of Towards Atmospheric Care, a long-term art-led research project by visual artist Hanna Husberg and researcher in ecology, photography and new media Agata Marzecova. The research and installation has been developed through the support of several artistic residencies and institutions, notably residencies at Ars Bioarctica Residency (Finnish Bioart Society, Kilpisjärvi, 2018-19), Torpet, Pro Artibus (2019), NKF residency, Stockholm (2020), Husberg’s Bernadotte scholarship at the Royal Art Academy, Stockholm (2019-20), Marzecova’s HIAP residency and a generous project grant from the Arts Promotion Center, Finland (2020). The project was first exhibited at Östra Galleriet, Royal Art Academy, Stockholm (14.3-14.6.2020).